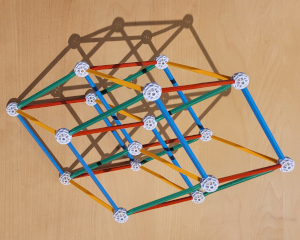

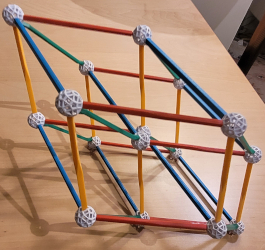

Our construction will not be the Schlegel diagram above, but rather a projection of the four-dimensional cube into 3-dimensional

space.

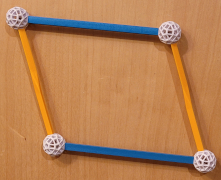

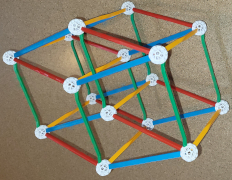

To begin, consider the cube above, which is viewed at an angle so that we may appreciate all eight of its vertices and twelve of its

edges. Note that the edges come in three sets of four parallel edges.

Note also that none of the six square facets of cube appears square (but the square next to it appears square).

That is because we are seeing a projection of the cube to two-dimensional space.

Because the center of projection is the camera lens rather than a point at infinity, there is some distortion, but there are three

pairs of parallel faces, with each pair consisting of isomorphic (congruent) parallelograms.

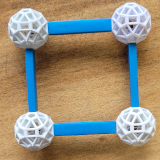

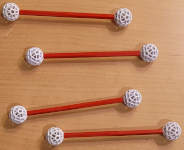

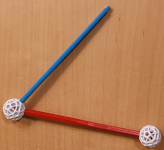

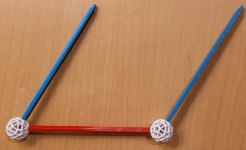

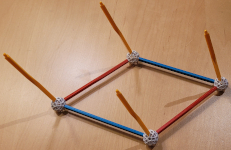

At the left below is a parallelogram, which is determined by the two lengths of the edges and their relative angle.

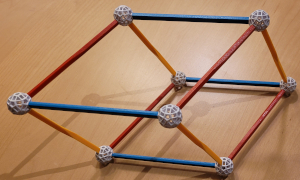

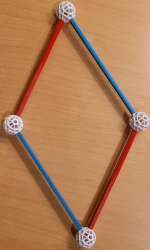

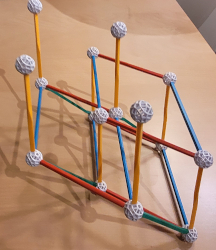

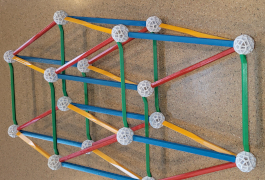

To make a 3-dimensional parallelipiped, you choose three directions for the three edges, then build each pair out to parallelograms,

and then complete into the full figure.

One is displayed second from the left below.

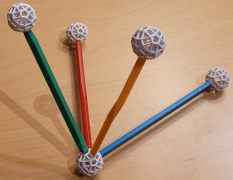

For this, we began with the rightmost zome, choose three edges (yellow, blue, and red struts) coming from it, and then built it

out.

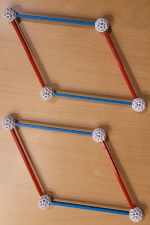

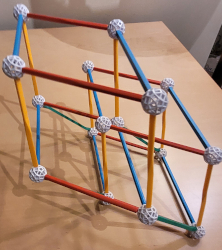

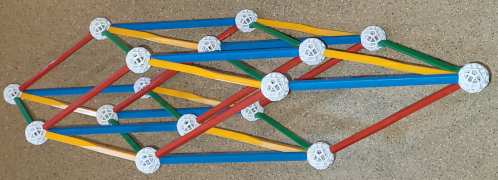

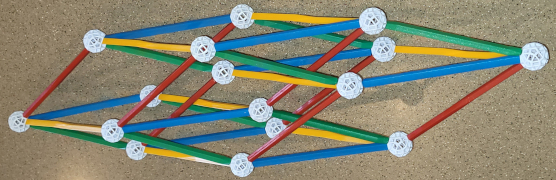

For the four-dimensional cube, we will pick four directions from a vertex and then similarly "build it out" (but not quite, see the

instructions below.)

This is the image of each of the four unit intervals (along each of the four coordinate axes) in R4 under the

projection map R4-->R3 sending the four-cube to the model.

We show this local configuration below at right.

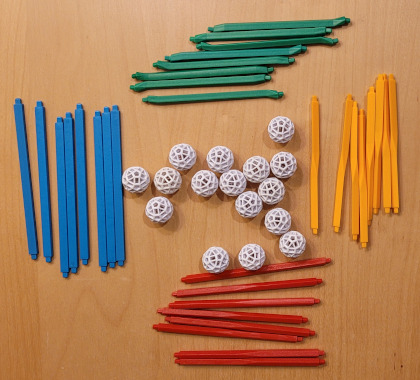

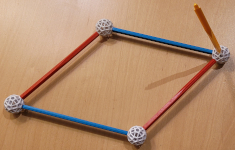

When you build your model below, there are three places where you make a choice of a direction for a new strut (blue, yellow, green).

Almost every choice is valid, and they each give a slightly different projection.

(Your model likely will not look exactly as mine does.)

|